I started Taste the dram so I could learn more about the spirits and lifestyle industry and grow my knowledge base. I also started the company so I could share my love for whisky, cigars, spirits and just the general lifestyle with whomever wants to read my written dribble. I have never dreamed that over the years we would grow and do interviews with so many knowledgeable industry people. On that note, today we have a very special interview with the co-founder Jerry Toth of To’ak Chocolates. If you didn’t’ know, To’ak is currently the world’s most expensive chocolate, but not based on gimmicks, but mostly purely on the process and attention as well as the quality of the product.

If you’ve ever wondered how a bottle of Whisky can cost over $1000.00 which serves 23 oz of brown goodness, and how a bar of chocolate can be upwards to $500 and serve maybe a 5-10 minute window, you don’t know chocolate. The craft behind making chocolate, well To’ak chocolate in particular, is almost as art. It’s not mass produced, it’s almost as watching Leonardo Da Vinci paint the Mona Lisa in real time. So without a due, please read the full story behind To’ak chocolate.

Jerry, let’s kick things off with the basics. Please tell us a little about yourself. Also, how long have you been working with chocolate?

Jerry, let’s kick things off with the basics. Please tell us a little about yourself. Also, how long have you been working with chocolate?

JT: I’m 39 years old, born in the Chicago area, graduated from Cornell University with a degree in Economics. After graduating I roamed Central and South America for about 5 years, working a series of odd jobs in multiple countries, until finally feeling the pull toward setting roots down. I did this in Ecuador in 2006, where I co-founded a rainforest conversation foundation called Third Millennium Alliance, along with an Ecuadorian woman and an American ecologist. The three of us met when we were living in Valparaiso, Chile a few years prior. As our flagship project in Ecuador, we created the Jama-Coaque Ecological Reserve, which currently protects 1,400 acres of tropical forest in coastal Ecuador, which I continue to manage to this day.

In terms of my work with cacao, I first started harvesting cacao in 2007 in the Jama-Coaque Reserve, but at that point I still didn’t know how to make chocolate. Initially I ate cacao the same way people did in Ecuador 5,000 years ago—while walking in the forest, a little hungry and a little thirsty, I pulled cacao pods off of trees, smashed the pod against a tree trunk, scooped a handful of the juicy wet seeds into my mouth, sucked on the pulp for a few minutes to extract the juice, then spat them out on the ground. In 2008, I first started cultivating cacao in the land immediately surrounding our house in the Reserve, and that was also the first year I started making chocolate from cacao harvested from the old feral trees in the forest above our house.

In terms of my work with cacao, I first started harvesting cacao in 2007 in the Jama-Coaque Reserve, but at that point I still didn’t know how to make chocolate. Initially I ate cacao the same way people did in Ecuador 5,000 years ago—while walking in the forest, a little hungry and a little thirsty, I pulled cacao pods off of trees, smashed the pod against a tree trunk, scooped a handful of the juicy wet seeds into my mouth, sucked on the pulp for a few minutes to extract the juice, then spat them out on the ground. In 2008, I first started cultivating cacao in the land immediately surrounding our house in the Reserve, and that was also the first year I started making chocolate from cacao harvested from the old feral trees in the forest above our house.

Every year I planted more cacao seedlings, and every year as the trees grew older, I learned how to manage them in each phase of their growth, starting with merely trying to keep them alive and happy in year one, then pruning them in years two and three, and starting to harvest in year four and onward. Recently I’ve been working on my grafting skills. This next year, one of my main focuses (in terms of upping my game in cacao farming) is to really dive deep into soil management and organic fertilization. I’ve personally planted five different micro-plantations of cacao and manage three additional old-growth plantations—all in the Jama-Coaque Reserve.

The cacao parcel I’m developing this year is the crème de la crème. It’s a joint project between To’ak, Third Millennium Alliance, and an agricultural university here in Ecuador—the Escuela Superior Politécnica de Manabí (ESPAM, for short). We call it a Noah’s Ark of ancient Nacional cacao. It’s a genetic bank that contains thirty grafted seedlings from each of the DNA-verified Ancient Nacional trees from Piedra de Plata. Within three years, each of these young trees will be able to provide enough cuttings to reproduce dozens of additional pure Nacional seedlings each year, which will then be distributed to any local cacao grower who wants to help save this historic variety from extinction.To’ak will also be able to make a very special limited edition of chocolate from this cacao—a 100% pure Nacional dark chocolate.

I started making chocolate in our off-the-grid Bamboo House, which we built with hand tools, in the middle of the forest. Our house didn’t have electricity, so I made chocolate by hand in the rustic style taught to me by our neighbors—at first very low-tech. I never even gave a thought about commercializing it—it was just for me and the other people who came to our Reserve to work. And yet, I noticed that everyone who tasted it (myself included) treated it almost like a religious experience, not just because of how it tasted, but because everyone intimately knew the land this cacao came from and they knew everything that went into making the chocolate. Once you become intimately connected to the land and the process that goes into it, tasting chocolate becomes almost a religious experience. I saw how powerful of an experience this was for people and wanted to bring this experience to people beyond the confines of our forest preserve. This is when I linked up with Carl Schweizer, who became my business partner and fellow co-founder of To’ak.

I started making chocolate in our off-the-grid Bamboo House, which we built with hand tools, in the middle of the forest. Our house didn’t have electricity, so I made chocolate by hand in the rustic style taught to me by our neighbors—at first very low-tech. I never even gave a thought about commercializing it—it was just for me and the other people who came to our Reserve to work. And yet, I noticed that everyone who tasted it (myself included) treated it almost like a religious experience, not just because of how it tasted, but because everyone intimately knew the land this cacao came from and they knew everything that went into making the chocolate. Once you become intimately connected to the land and the process that goes into it, tasting chocolate becomes almost a religious experience. I saw how powerful of an experience this was for people and wanted to bring this experience to people beyond the confines of our forest preserve. This is when I linked up with Carl Schweizer, who became my business partner and fellow co-founder of To’ak.

Jerry who else is involved in this business venture with you?

Jerry who else is involved in this business venture with you?

JT: Carl Schweizer and I co-founded To’ak together. I had a crazy dream and Carl is the one who helped me make it a reality. Without Carl, To’ak would have never been born. Carl is Austrian, but like me, he’s lived in Ecuador for over a decade, and is married to an Ecuadorian woman, Dennise, who is To’ak’s general manager (To’ak is kind of a family business). The first thing about Carl is that he’s a design genius—everything that is beautiful and elegant about To’ak—from our packaging to our website and everything in between–was created by Carl. And yet, in his heart he is a chocolate maker. Carl and I make our chocolate together and are intimately involved in every single element of the production process. Another thing to note about Carl is that he is one of those people with an extremely refined palate. One of my favorite parts of this job is sitting down with Carl and tasting our chocolate, and then working together to write the tasting notes.

The other key person is Servio Pachard. Servio is a fourth-generation cacao farmer and one of the top organic agroforestry gurus in Ecuador. I was introduced to Servio in 2007, right when our conservation project was getting underway. He invited me and some of the other people I started the foundation with to stay at his farm for a few days, which had a big impact on me. Servio is the quintessential practitioner of sustainable agroforestry, and his farm (Finca Sarita) is like the Garden of Eden—it is a true food forest. If you’re hungry, all you need to do is wander the forest that surrounds Servio’s house and pull food off the trees. The food forest I designed around our house in the Jama-Coaque Reserve was inspired by Servio’s farm. I wrote about Servio at length on my blog, where I also interviewed him at (http://nacionalcacaoconservation.org/2017/05/servio-pachard/).

When it came time to start To’ak, Servio is one of the first people I talked to. He was the one who brought Carl and I to Piedra de Plata. Ever since, Servio has been To’ak’s Harvest Master, and we built our cacao fermentation and drying installation at his farm, where I now have reason to spend a lot of time for work. Usually I stay overnight there and sleep in a tree house he built in the top of a massive mango tree.

In Piedra de Plata, we work with 14 cacao growers, who have become friends and also mentors to me, in terms of farming cacao.

What does To’ak mean? Does it have any special meaning behind it?

What does To’ak mean? Does it have any special meaning behind it?

JT: To’ak is a fusion of two words in an ancient Ecuadorian dialect that mean “earth” and “tree”, which is our take on the French term terroir. As many people know, terroir is a key factor in the flavor profile of a given wine. What people often don’t know is that terroir is equally important in shaping the flavor profile of single origin dark chocolate. One of our primary goals with every edition of chocolate that we make is to highlight the unique soil and climate characteristics of one very special valley in Ecuador, called Piedra de Plata. When you taste To’ak chocolate, you are tasting the land and weather of this valley—albeit polished a bit through many hours and days and even years (in some cases) of our production process.

Jerry, our readers know a thing or two about aging whisky or other spirits. How do you incorporate barrel aging in your products?

Jerry, our readers know a thing or two about aging whisky or other spirits. How do you incorporate barrel aging in your products?

JT: As most whisky connoisseurs are well aware, 70-80% of the flavor of a whisky is extracted from the wood of the barrel it was aged in. The whisky literally draws lignins and lactones and hemicellulose from the wood, as well as the remnants of sherry or bourbon, depending on what the barrel previously contained. This same process applies to chocolate aging. Cacao beans are roughly 50% fat. If you press a cacao bean with a great deal of strength, you can actually extract this fat, which is referred to as “cacao butter.” One of the interesting qualities of the fatty oils in cacao is its remarkable ability to absorb other aromas.

Anyone who has purchased a bar of To’ak online is most likely familiar with the storage instructions we remind each of our customers. In addition to not storing your dark chocolate in a freezer or refrigerator, we also remind people to protect their chocolate from other strong odors. If you want to experiment with this phenomenon at home, try storing an open bar of chocolate in the vicinity of a sliced onion. Within a very short time, the aroma of the onion will be impregnated in the chocolate. (Please don’t use To’ak Chocolate for this experiment). The inverse of this experiment is to store chocolate with pleasing aromas. We do this in several ways. In some cases, we age our chocolate in barrels that previously contained cognac, whisky, port, etc.

In these cases, the chocolate extracts the aromas and flavors from the spirit as well as the wood—just as a whisky like Aberlour or Macallan extracts aromas and flavors from sherry casks. We also age our chocolate in various different types of Ecuadorian wood. In this case, the wood has not been impregnated with spirits—the aromas and flavors that the chocolate extracts are solely from the wood itself, and in some cases this can lead to unique and surprisingly charismatic chocolate. Our Andean Alder edition is the best example of this, which has taken on strong vegetal notes of things like oregano, along with campfire, tobacco, even roasted beef….in an Ecuadorian dark chocolate! It sounds weird, and it is, but it somehow works. This edition is an in-house favorite—it’s the chocolate that Carl and I can’t stop eating once we start.

There are a number of niche chocolate companies in the market. What are you doing to stand out and be more unique than others?

There are a number of niche chocolate companies in the market. What are you doing to stand out and be more unique than others?

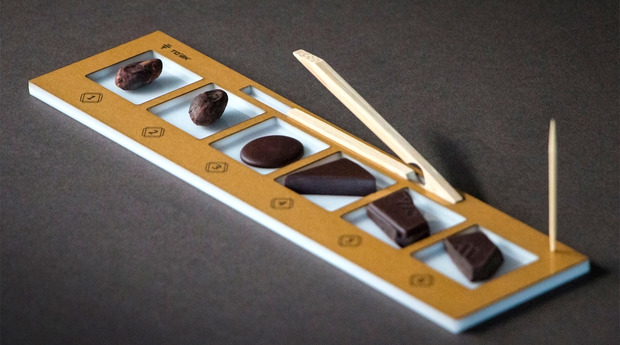

JT: Our goal is to make chocolate at a level that has never been done before, in terms of everything from the genetics of the cacao we use, through the specific production steps, and then ultimately presenting this chocolate to our customers not in the mere form of a bar, but as a work of art, as something that goes so far above and beyond what people traditionally associate with chocolate. We use the oldest and rarest variety of cacao on earth to produce extremely limited editions of single origin Ecuadorian dark chocolate, oftentimes aged in specialty casks or Ecuadorian wood vessels for a period of years. Each bar is packaged in a handcrafted Spanish Elm wood box with the individual bar number engraved on the back. It includes a 116-page booklet and specially-designed tasting utensils.

Why go to all of this trouble? Let’s look at this in a historical context. People often overlook the fact that chocolate was considered sacred by almost every single culture it touched for thousands of years. It was a delicacy reserved for priests and warriors and royalty, and in some cultures it was even used as currency. According to written records, the price of a hand-woven blanket in the Aztec kingdom was one hundred cacao beans. At the current commodity price of cacao, this equates to $0.23 for something that took up to 200 hours of labor to produce. The exalted value of chocolate didn’t fundamentally change until the 20th century, with the advent of industrial food production. Like so many other things we eat, chocolate was cheapened by mass-production. It became synonymous with $1 candy bars—a quick fix of sugar and fake milk and a bunch of chemicals that nobody can pronounce, mixed with a bit of low-grade cocoa powder.

This is a symptom of a much greater issue, which is what happens when you have a world of 7.6 billion people, where everyone wants their chocolate and eat it too. It has eroded the quality of what we eat, it renders it almost impossible for farmers (of any crop) to make a reasonable living, and it also generally renders life and culture as a more vapid, homogenized experience lacking in meaning. When I set out to start a business (which eventually became To’ak), I gave myself one mandate: to make something that has meaning, and that promotes meaning. We’re too small to effect change on a massive cultural scale—but at least we’re able to effect change in one very special craft industry, which is chocolate. And one way or another, we’re doing it. We are radically altering the way people value and perceive and experience chocolate, and we’re doing it in a way that nobody else is.

This is a symptom of a much greater issue, which is what happens when you have a world of 7.6 billion people, where everyone wants their chocolate and eat it too. It has eroded the quality of what we eat, it renders it almost impossible for farmers (of any crop) to make a reasonable living, and it also generally renders life and culture as a more vapid, homogenized experience lacking in meaning. When I set out to start a business (which eventually became To’ak), I gave myself one mandate: to make something that has meaning, and that promotes meaning. We’re too small to effect change on a massive cultural scale—but at least we’re able to effect change in one very special craft industry, which is chocolate. And one way or another, we’re doing it. We are radically altering the way people value and perceive and experience chocolate, and we’re doing it in a way that nobody else is.

I should also add that we are one of the only truly “tree-to-bar” chocolate makers out there. Most “bean-to-bar” chocolate makers live in industrial countries more than 2,000 km from the nearest cacao tree. They import their beans from far away. Maybe they visit a cacao-producing region every now and again, but they don’t watch a cacao tree grow from seed to maturity, and tend to it like a child all along. They don’t have that intimate connection with the land that cacao is from. At To’ak, the connection with the land and the trees themselves—day in and day out—is extremely important to us.

Can you tell us a bit about the process from the initial gathering of the cacao to the actual product in the end?

Can you tell us a bit about the process from the initial gathering of the cacao to the actual product in the end?

JT: To break the process down into the most basic terms, you start by harvesting the fruit of the cacao tree, which is a shade-tolerant tree native to the tropical forests of Ecuador. Next, you ferment the seeds, which are encased in a sweet white flesh in large wooden boxes for anywhere from three to seven days, depending on the cacao variety and the flavor/aroma objectives of the chocolate maker. The longer you ferment, the astringency of the beans will be pacified but if you ferment for too long, you also start to lose flavor and character. If you ferment for too short of a time, you may have robust flavors (especially floral flavors) but this may come at the expense of astringency and/or acidity, which may conceal the more subtler elements of flavor and aroma. So the trick is to find that happy medium in which astringency is pacified but flavor remains complex and dynamic.

The next phase is to dry the seeds (which are now called “beans”) in structures that resemble a greenhouse, using sin and air. The beans are then carefully roasted, de-shelled, and ground into tiny bits, which are called nibs. In the most basic sense, dark chocolate is made by further grinding and liquefying the nibs through heat and mixing them with varying amounts of sugar. Then comes something called conching, which is actual one of the most important determinants of the final flavor profile. Conching is essentially the mechanical churning of chocolate—when it is in heated, liquid form—for periods of hours and sometimes even days. This process expels volatile acids from the chocolate into the air, which has the general effect of smoothening out the flavors and aromas (rounding off the corners, so to speak) but also shaping the flavors and aromas. In our experience, working specifically with Nacional cacao from Ecuador, shorter conch times tend to produce a more floral aroma.

Extending the conch times can transition some of those notes into fruity notes. And if you keep conching it even longer, the fruity notes start to soften into a caramel undertone that is smooth but that may lack charisma and complexity. Again, the fun part of the job for us is to find that magic point along the spectrum where the balance between character and approach-ability is optimized, given our particular objectives with a given edition.

Is not all cacao created equal?

Is not all cacao created equal?

JT: There is just as much variation in quality and flavor of cacao as there is in wine—if not more so.

The vast, vast majority of cacao in the world is considered “bulk” (i.e., low-grade) cacao. Only 5% is classified as “fine flavour” cacao, and over half of the world’s “fine flavour” cacao comes from Ecuador. But even the quality of “fine flavour” cacao widely varies according to more specific genetic and terroir distinctions and especially in terms of processing methods. High-quality cacao that is not properly fermented or dried will invariably produce a low-quality chocolate. And unfortunately, a surprising amount of “fine flavour” cacao is very poorly fermented and dried, because farmers often have little incentive to take this step seriously. Often in Ecuador you see cacao laid out on the side of a road to dry, which is obviously not a good practice. This is why we ferment and dry our cacao ourselves, and take it extremely seriously.

In the realm of “fine flavour” cacao, the most celebrated cacao variety is Nacional from Ecuador, which is what we use. It is both the oldest and rarest variety of cacao on earth.

Nacional goes back 5,300 years to the earliest known cacao used by humanity. By the 1800s, it was the most highly-sought cacao in the world—prized for its floral aroma and complex flavor profile. Then in 1916 a disease called Witches Broom devastated cacao throughout Ecuador. Up until about ten years ago, pure Nacional cacao was believed to be extinct. We found a valley with old-growth cacao trees that matched the profile of ancient Nacional cacao. We DNA-tested the trees and they were a 100% genetic match. This remote valley (Piedra de Plata) is where we exclusively source our cacao. These same trees are what we’re using to graft the young seedlings that we’re reproducing in the Jama-Coaque Reserve.

The flavor and aroma profile of a given dark chocolate is influenced by the variety of the cacao, the soil and climate conditions in which it was grown (i.e., terroir), and the production methods used to convert it into chocolate. Here are but a few examples of how these elements shape what you experience inside your mouth.

- Dark chocolate from Ghana, which is primarily produced from the Amelonado variety, is kind of like the Merlot of the dark chocolate world. It often has a mild tannic structure, which makes it very approachable, particularly to people who are new to dark chocolate and haven’t yet developed an appreciation for its inherent bitterness. It’s flavor profile is primarily dominated by classic “chocolatey” notes, occasionally with a trace of red fruits.

- Criollo dark chocolate from Venezuela is also known for its relatively mild tannic structure, but offers an additional layer of complexity overlaid onto a pleasing, nutty base.

- Criollo dark chocolate from Madagascar, on the other hand, is known for a rather lively citric acidity—akin to a fruit-forward New World wine. If you’re organizing a tasting of dark chocolate from various different growing regions throughout the world, Madagascar chocolate is a good one to include, simply because it’s acidic fruit-forward profile is so distinctive. For this same reason, however, it also has a reputation for one-dimensionality.

- Dark chocolate from Pacific islands like Bali and Papua New Guinea is another distinctive origin to include in a comparative tasting, on account of its smokey/tobacco characteristics.

- Dark chocolate from Nicaragua can often be distinguished by its prominent earthy notes. However, an “earthy” chocolate that veers toward the “dirt” end of the spectrum is most likely due to moldy cacao beans rather than variety and terroir. Cacao that is harvested and fermented in especially wet and humid climates, such as the Amazon, is more prone to producing undesirable “dirt” notes. On the other hand, grassy/vegetal notes, which are consequences of both terroir and production methods, often lend a fascinating freshness to the palate.

- Although the writers of this guide are admittedly biased, it is fair to say that Nacional cacao from Ecuador most likely claims the greatest degree of complexity among all dark chocolates. Floral, fruity, nutty, and vegetal/earthy notes are all characteristics of Nacional cacao, and in some cases can all be perceived in the same bar of Ecuadorian dark chocolate. However, their relative levels of expression do highly depend on terroir and production methods. In our experience at To’ak—without going in to too great of detail—we have found that shorter fermentation times and shorter conch times both serve to highlight the floral components, with orange blossoms and jasmine the most frequently cited. As both fermentation times and conch times grow longer, the flavor profile starts to veer toward the fruity side of the spectrum, although this only holds true up to a certain point. Notes of red fruits (cherry, raspberry, cranberry), dark fruits (plum, raisins, black mission fig), citrus (often grapefruit), and even tropical fruits (banana, occasionally mango) are all capable of presenting themselves. Earthy and grassy notes are another feature found in Ecuadorian dark chocolate, which sometimes moves into the woody realm of oak, pine, even eucalyptus.

What different products are currently available for purchase?

What different products are currently available for purchase?

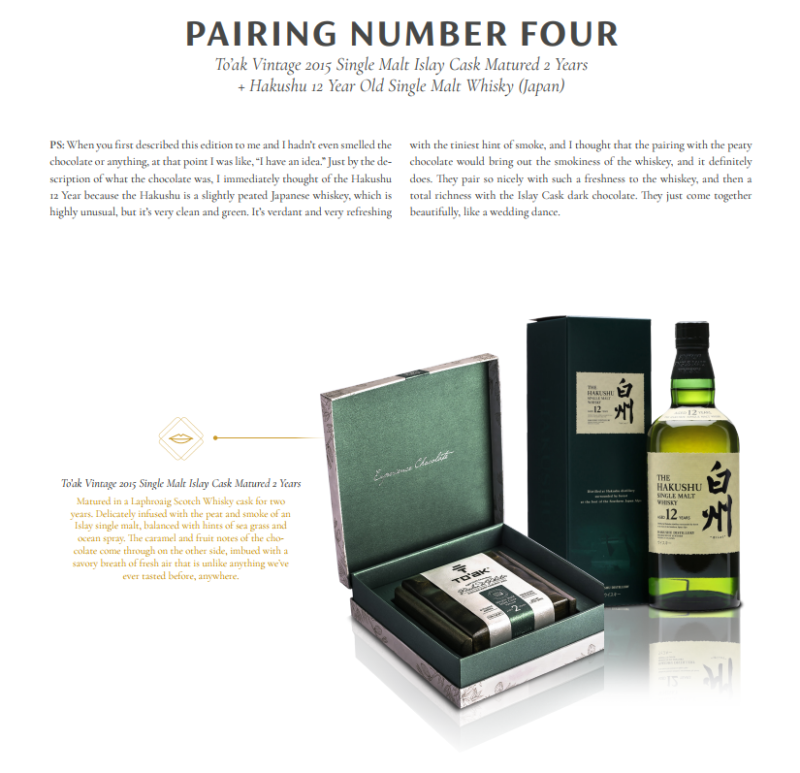

JT: Vintage 2015 Single Malt Islay Cask Matured 2 Years – 73% Cacao ($355)

Matured in a Laphroaig Scotch Whisky Cask for two years. Delicately infused with the peat and smoke of an Islay single malt, balanced with hints of sea grass and ocean spray. The caramel and fruit notes of the chocolate come through on the other side, imbued with a savory breath of fresh air that is unlike any- thing we’ve ever tasted before, anywhere.

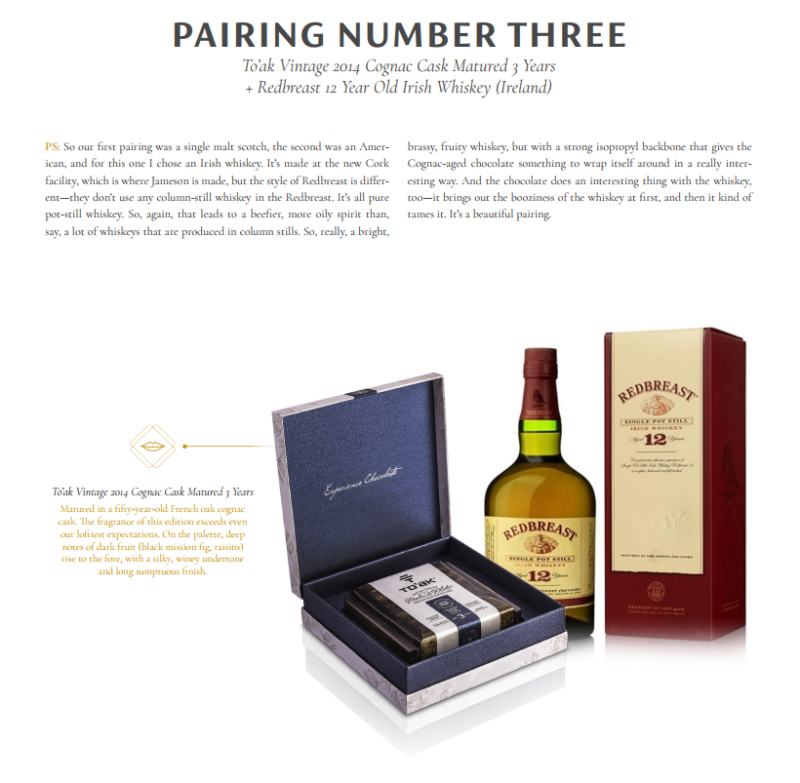

Vintage 2014 Cognac Cask Matured 4 Years – 81% Cacao ($385)

The flagship edition of To’ak’s chocolate-aging program. Vintage 2014 from Piedra de Plata, matured in a fifty-year-old French oak cognac cask for four years. The fragrance of this edition exceeds even our loftiest expectations. On the palette, the prominent notes of dark fruit (black mission g, raisins) continue to deepen, with a silky, winey undertone and long sumptuous finish.

Vintage 2014 Andean Alder Matured 3 Years – 81% Cacao ($335)

Among all six different types of Ecuadorian wood that we’re aging our chocolate in, we found that Andean Alder imparts a prominent aromatic note unlike any other we’ve ever experimented with—a charismatic flourish that works intriguingly well with our 2014 harvest. Campfire, roasted beef, spice-herbal transition (oregano, rosemary), a fruity sweetness comes in with acidic cranberry and is punctuated with creamy spice on the finish. This chocolate is for more experienced palates.

EL NIÑO HARVEST 2016 – 78% Cacao ($295)

Start with heirloom Nacional cacao from Piedra de Plata in Ecuador, add torrential El Niño rains during flowering and fruit set, followed by an unexpected drought during the critical ripening period, and top it off with an unusually late harvest forced by a 7.8 magnitude earthquake. The result? Wood and a touch of flowers on the nose, with an earthy play of buttery citrus, red fruits, ripe banana, and a trace of eucalyptus on the palate. This is a delightfully challenging difficult chocolate to figure out.

Nowadays, brands are utilizing social media channels such as Instagram and Facebook to build brand awareness. How have you used your social media channels to grow your business?

JT: We got a slow start with social media, and are just finally starting to catch up. We primarily use social media to educate people about the finer nuances of cacao farming, cacao genetics, chocolate making, and aging.

Jerry, we know that you are involved in social and environmental philanthropy. Can you express to our readers, why this is so important to you, and how To’ak is giving back?

Jerry, we know that you are involved in social and environmental philanthropy. Can you express to our readers, why this is so important to you, and how To’ak is giving back?

JT: I’ve been working as a conservationist longer than I’ve been working in chocolate. I am co-founder and still active direct the nonprofit rainforest conservation foundation Third Millennium Alliance (TMA), where we have preserved over 1,400 acres of tropical forest in coastal Ecuador—considered the most threatened tropical forest in the world. One of our first projects with TMA was planting cacao trees on deforested land surrounding our forest preserve, and from there, my obsession with cacao farming was born.

One of the reasons I started To’ak was because I saw the limitations that nonprofit organizations face when trying change things—mainly because there is so little money available for nonprofits. To’ak was an attempt to create a for-profit business with a positive ecological impact. One of our driving priorities at To’ak is saving the world’s most ancient variety of cacao from extinction. This variety (called Nacional) was believed to be extinct as of ten years ago. We found a valley with old-growth trees that matched the profile of ancient Nacional, so we conducted DNA analysis on the trees and confirmed that they are a 100% genetic match. Now we’re grafting budwood from these old trees onto new seedlings, which we’re planting in a protected area of the Jama-Coaque Reserve (managed by TMA), which we are using to resurrect this variety. We call this the Noah’s Ark of ancient Nacional.

Once these young trees reach maturity, we will take budwood from them and graft them onto new seedlings, which will be 100% genetically pure Nacional. We’re going to distribute these seedlings to any farmer who wants to grow this historically-prized heirloom variety, globally renowned for its quality and also for its extremely low yields. The cacao growers we work with are paid the highest price per pound in Ecuador, and we provide them with organic and fair trade certification for all of their products.

If you were to use your expertise in this industry and behind your product, which particular chocolate product would you pair with the following whiskies and why:

If you were to use your expertise in this industry and behind your product, which particular chocolate product would you pair with the following whiskies and why:

JT:

Sherry Finished Cask Scotch, (i.e Glendronach, Glenmorangie, Aberlour)

Sherry Finished Cask Scotch, (i.e Glendronach, Glenmorangie, Aberlour)

Aberlour is one of my favorite whiskies to pair with To’ak, particularly the 16-year and 18-year, and also the A’bundh if it’s slightly diluted. And more generally, sherry finished cask scotch is possibly the most user-friendly scotch to pair with To’ak. I recently co-hosted a chocolate-whisky pairing event with Macallan, which is a brand I hadn’t deeply explored in the past, and was pleasantly amazed at how well Macallan and To’ak pair together, particularly their sherry-aged whiskies. I would put Aberlour and Macallan close to the top of the list for To’ak pairing partners, and Glenmorangie, too–although it’s been three years since the last time I’ve paired Glenmorangie with To’ak and I need to go back to it to refresh my memory on that one. I have not paired Glendronach with To’ak but would like to.

Peated Scotch (i.e. Laphroaig, Bowmore, Ardbeg)

Peated Scotch (i.e. Laphroaig, Bowmore, Ardbeg)

Please refer to the introduction in the attached document, titled “Seven Grand Pairing Recommendations”, for the interesting background on To’ak chocolate and peated whisky. Laphroaig is one of our all-time favorites, which is why we aged our 2015 vintage in a Laphroaig barrel for two years, which is arguably our best chocolate ever (and which pairs very well with Laphroaig, although it also pairs very well with non-peated whiskies, port, PX sherry…our Laphroaig-aged edition is surprisingly our most versatile chocolate to pair spirits with). I love Ardbeg, but it’s not the best pairing partner for our current range of chocolate—and I’m not sure why. Caol Ila is good, Lagavulin (another one of my all-time favorites) can also work.

International Whisky (i.e. Yamazaki, Paul John Indian Whisky, Kavalan)

International Whisky (i.e. Yamazaki, Paul John Indian Whisky, Kavalan)

American Bourbon ( i.e. Elijah Craig, Makers Mark, Wild Turkey)

Japanese whisky offers a few very good pairing partners for To’ak. Yamazaki 18-year is one of the whiskies that we most liked to pair our 2014 edition with, shortly after it was produced. Hibiki and Hakushu also pair well. (Interestingly, the pairing master at Los Angeles’s preeminent whisky bar, Seven Grand, picked the Hakushu 12-year as his favorite whisky to pair with our Vintage 2015 Islay Single Malt Matured 2 Year edition (i.e, our Laphroaig-aged edition)

In the American whisky realm, a lot depends on age. Young bourbons tend to have too much heat for our chocolate. But once they’ve been properly aged, and some of those younger flavors start to transition toward caramel and vanilla a bit, then they start to work. I find that Angel’s Envy lends our chocolate an interesting banana note. Eagle Rare works well. Buffalo Trace works well, and so does Pappy Van Winkle, which of course is distilled at Buffalo Trace. Seven Grand picked Russell’s Reserve 6 Year Old Rye as their favorite pairing for our El Nino Harvest 2016 edition.

Irish whiskey is probably the easiest whisky to pair with To’ak. If you want to play it safe and get a bottle that you know will work with pretty much every edition of To’ak, pick pretty much any decent bottle of Irish whiskey and it should work well, which I believe can be attributed to the process of triple distilling. Some of our favorites are Tyrconnel, Redbreast 12 year, and even just your standard Bushmills and Tullamore Dew pair extremely well.

Can you give us a sneak peak into any future endeavors, initiatives or products?

Can you give us a sneak peak into any future endeavors, initiatives or products?

JT: Absolutely. We are currently awaiting the arrival of an ex-port, ex-sauternes, ex-bourbon, ex-tequila, ex-Pedro Ximenez Sherry barrels—all are currently on a ship headed for Ecuador, and all of which will be used to aged our chocolate. So in 1-3 years, you will start to see those editions being released. In the more near future, we’re releasing a new edition aged in a very special Ecuadorian wood, which I am not yet at liberty to identify. This spring we’re also releasing an edition aged with Cambodian Kampot pepper, which is an edition that everyone at To’ak has fallen in love with.

Your company has been known to do tasting events where you pair whisky and chocolates. What is it about these two products that creates an almost seamless pairing? What attributes does the chocolate enhance in the whisky?

JT: Dark chocolate and whisky share many of the same primary and secondary flavor characteristics—fruity, floral, nutty, honey, caramel, citrus, etc. And dark chocolates and whiskies that have overlapping flavor notes tend to play very well together on the palate. Much of this can even be predicted based on the variety/terroir of the chocolate and the production methods of the whisky. For example, Ecuador’s famous cacao variety Nacional is known for its unique combination of fruity and floral notes. This type of dark chocolate pairs extremely well with a sherry-finished single malt, such as Macallan or Aberlour, because of the fruity notes that a sherry cask imparts on the whisky, as well as those supplementary notes of honey or nuttiness, which is an easy point of common ground with dark chocolate. Then sometimes there is a subtle note in either the chocolate or the whisky which is suddenly coaxed into a more prominent role with both are paired together, such as a citrus or jasmine note. I’ve noticed the Angel’s Envy brings out a really interesting banana note in our chocolate, whereas Pappy Van Winkle brings out a candied apple note that is otherwise dormant in our chocolate.

And then there are some chocolate-whisky pairings which, on the surface, are counterintuitive. I originally assumed that heavily-peated whiskies would not be good pairing partners with our chocolate, for fear that the peat would overwhelm the more delicate fruity and floral notes of the chocolate. Fortunately I was proven wrong about this, and Laphroaig was the whisky that did it. The interesting thing about Laphroaig is that there are hints of fruit underneath that smoke, so this provided some common ground. But also, those vegetal sea notes in Laphroaig tend to add a very interesting savory note to our chocolate. The weird beauty of this marriage is what inspired me to import a Laphroaig barrel to Ecuador and age our chocolate in it for a few years, and this edition [Vintage 2015 Single Malt Islay Cask Matured 2 Years] is, in my opinion, To’ak’s finest creation. A successful pairing between chocolate and whisky is much like a successful pairing between two lovers. You need to have some things in common, but if you’re basically carbon copies of each other, then it doesn’t work. It’s the things you don’t have in common that generates that sense of mystery and keeps the romance alive.

How do you pair whisky with chocolate?

JT: Think of it as an arranged courtship between two soon-to-be lovers, and you have been given the task of bringing them together. Start out by carefully tasting the dark chocolate on its own. Next, carefully taste the whisky on its own—exploring both aroma and flavor. Now, once you have an idea of their individual personalities, it’s time to bring the two together, in a three-step process.

- First, place a piece of dark chocolate in your mouth and allow the melting process to get underway. With To’ak chocolate, this usually takes about ten seconds.

- Then, take a small sip of the whisky, bathing the chocolate in your mouth for another few seconds.

- Lastly, swallow the whisky but keep the chocolate in your mouth, allowing it to completely melt, and open yourself up to the unexpected evolution of flavors that occurs. In the case of cheese, there is no way to separate the two once they’ve been mixed inside your mouth. Simply enjoy this marriage to the fullest.

As usual, whisky should be served neat or, in some cases, with a very small addition of water—especially if it’s cask strength.

Anything else you’d like to share with our readers?

JT: This applies to the question about what distinguishes us from other chocolate makers out there. One major differentiator is the variety of cacao that we use, and the great lengths we have gone to search, research and genetically select this cacao. The cacao variety we use is called Nacional, which goes back 5,300 years to the earliest known cacao used by humanity. By the 1800s, it was the most highly-sought cacao in the world—prized for its floral aroma and complex flavor profile. Then in 1916 a disease called Witches Broom devastated cacao throughout Ecuador. Up until about ten years ago, pure Nacional cacao was believed to be extinct. We found a valley with old-growth cacao trees that matched the profile of ancient Nacional cacao. We DNA-tested the trees and they were a 100% genetic match. This remote valley (Piedra de Plata) is where we exclusively source our cacao. These same trees are what we’re using to graft the young seedlings that we’re reproducing in the Jama-Coaque Reserve.

Very nice article. I absolutely love this website. Keep writing!